Technology companies all face similar issues when it comes to their product portfolio:

- Relatively short product life-cycles

- Need to continually innovate

- Uncertainty of outcomes

- Build or Buy decisions

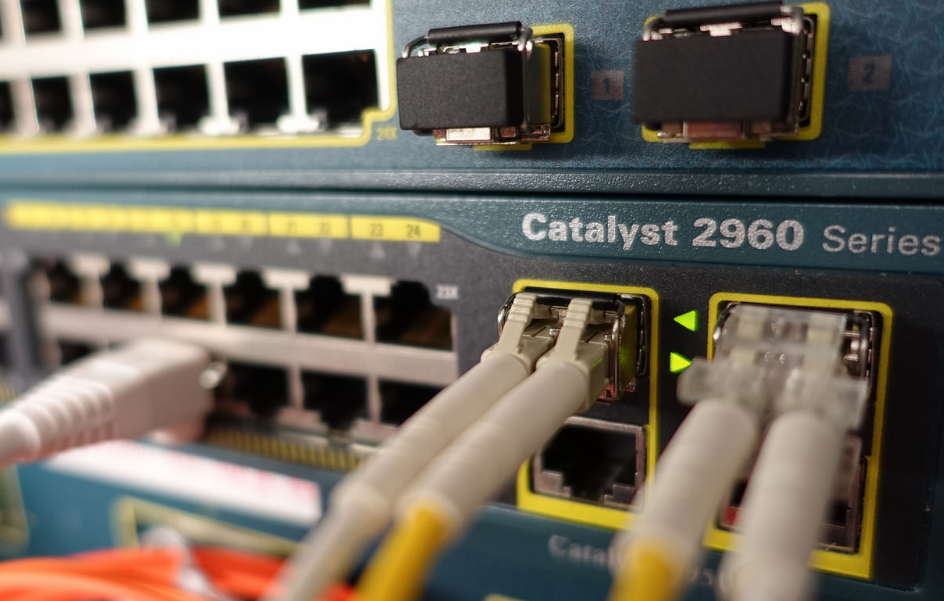

We took an outsiders view of Cisco, and its major product lines, excluding its services business which is becoming more important, but will not require major resource investment decisions.

Product information we considered while developing the model included:

- Size of market

- Point in product life-cycle (when it was released)

- Typical life-cycle length for the type of product

- Investment required to develop new product with similar profile

- Latest date when a product would still be viable

- Acquisition cost of companies/products in the market

The data is not exact, but strategy development does not require precise forecasts to give you useful directional guidance.

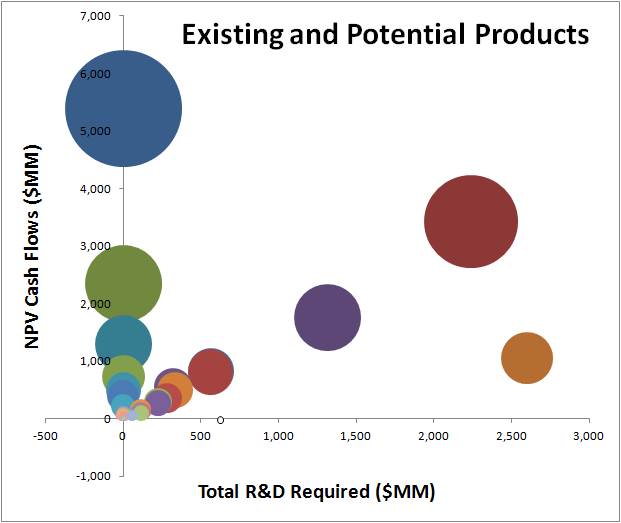

If we look at the existing portfolio and new product development (NPD) by R&D (or acquisition cost) required (on horizontal axis), and the risk-adjusted Net Present Value (NPV) of the cash flows for each opportunity, it looks like this:

The potential products would be pre-vetted with the usual process to see that they fit within the overall company strategy, that the company has or can acquire the necessary organizational capabilities to develop and deliver the product, and uncertainty has been considered. In other words, all of the considered projects would be done if resources were available. Also note that the values are risk-adjusted, with at least three cases made for each forecast.

The big provisional note there was, “…if resources were available.“

There are no companies with infinite resources, and if there was one, it would have acquired all the others and owned the entire market. Even a company as large as Cisco has to control its spending on new products. In the most recent quarter, it spent $5.6B on R&D, which was 15% of its product revenue of $37B.

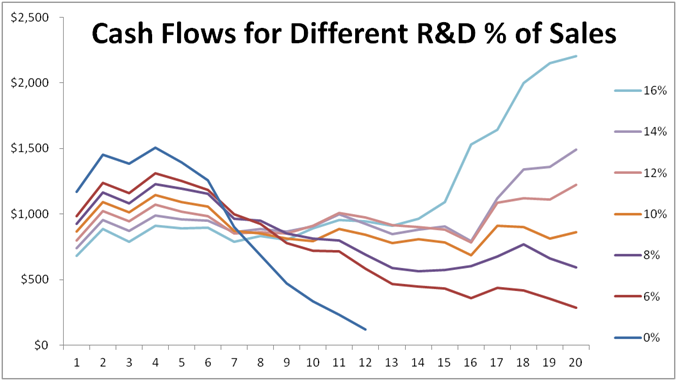

I wanted to see if they were spending the right amount, if they wished to achieve near and long-term growth goals. Using npv10’s Portfolio Optimizer, it was simple to set constraints on R&D spend as a percentage of the resulting cash flows. We ran seven different cases, with R&D as a percent of product revenue ranging from 0% to 16%. Once data was in, it took a little over an hour to run this set of analyses.

Each scenario selected a different set of new products with different start times (within the time-constraints allowed). Sometimes the scenario decided an acquisition would be more appropriate, and other times not. An acquisition may speed things up, but they also come at a higher cost because much of the development has been de-risked.

The results were interesting. Obviously cutting off all R&D spending helped near-term cash flow, but also dramatically impacted the future as existing products reached the end of their competitive life-cycle. Spending the most on R&D constrained cash flow over the first few years, but then dramatically increased as all of the new products entered their markets and generated revenue (which in turn provided more cash flow for future R&D). It also showed how almost all of the cases resulted in the same cash flows 2 ½ years out, but had vastly different numbers leading up to that time and afterwards.

We did not consider additional goals (such as growing revenue, paying dividends, improving margins, etc.) or constraints (headcount resources below some level, number of simultaneous product launches, etc.) but those can rapidly be layered onto the analysis.

In the end, your company needs to decide what your corporate goals are, and what’s holding you back from achieving them. It’s up to us to help you quickly and optimally determine various paths forward and the trade-offs among them.